On Influences and Lineage

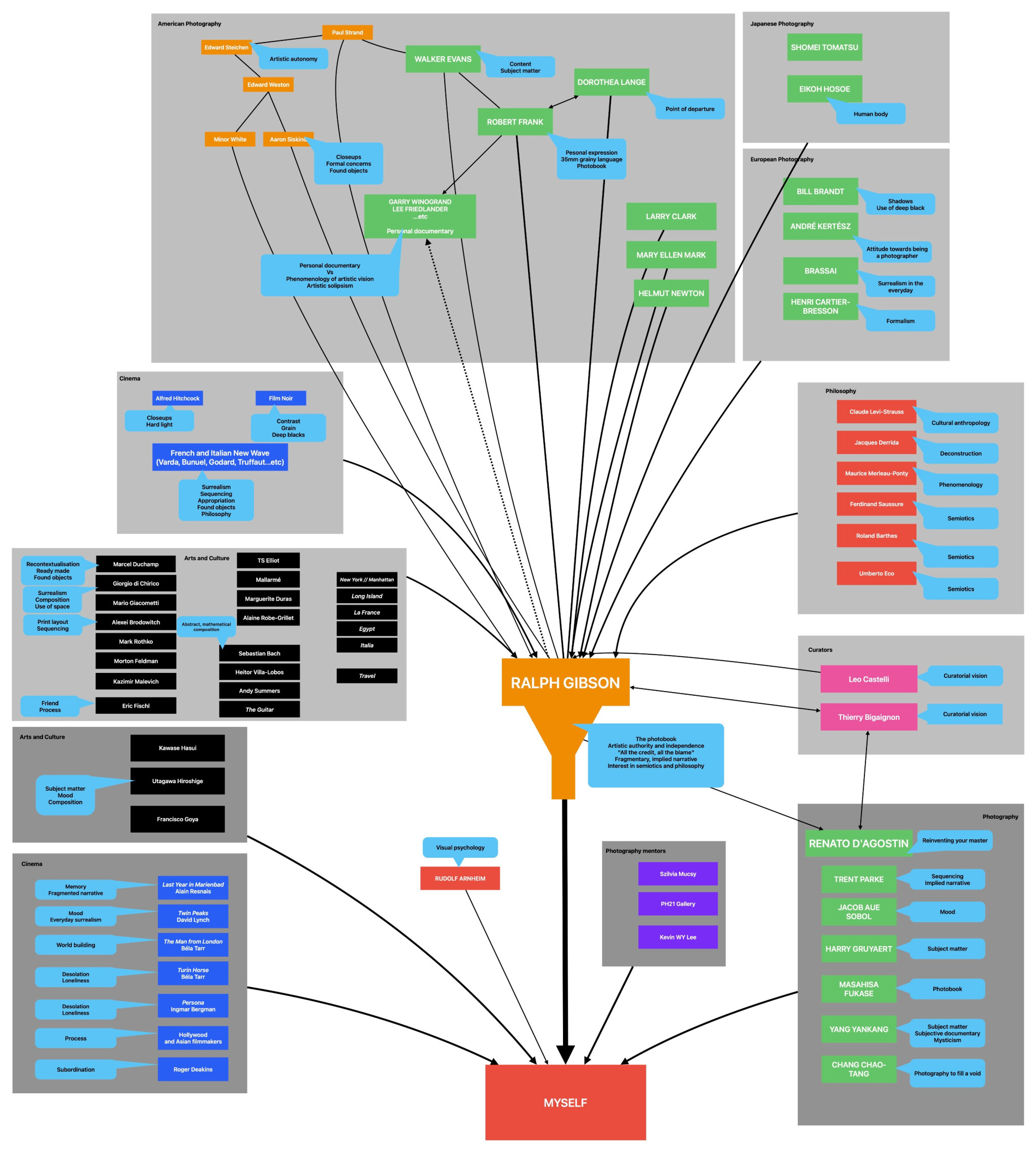

The pervasive myth of complete originality in Western culture can burden emerging artists, as though admitting an influence was giving up on individuality and authenticity. Yet I believe art is never created in a vacuum. Facing our lineage is not a weakness but a necessary acknowledgement of the tradition we inherit. We contribute our voices to the ongoing discourse by building on the groundwork others have laid. To understand my artistic evolution, I feel compelled to trace a personal and introspective map. I’m not aiming for academic rigour or complete exhaustion, but to create a chart of influence as a source of divergence.

The Encounter with Photography

My photography journey wasn't a sudden revelation; it came later in life as an organic discovery. My time in the film industry, especially the early years, was mostly about technical and organisational complexity, minute workflow issues, and a complete subordination to everyone else’s vision when making artistic decisions. Later, the immersion in cinema offered a broader understanding of narrative and visual storytelling, occasionally working with world-class directors and creatives—George Miller, Jackie Chan, Stanley Tong, Guo Fan, Lee Byung-Hun or Roger Deakins—exposing their problem-solving processes. I followed film work to satisfy my restless curiosity and need for personal growth on five continents. Despite years of photographs and diary entries, my understanding of photography remained limited to snapshots and the distant ideal of National Geographic.

However, a need for personal expression was already developing, and a somewhat chance meeting with Chang Chao-Tang’s surrealism in his two-volume Time: Images […] made an initial impression. It was an early sign that photography might be my clearest, most resonant language, but I was lacking a starting point. The real breakthrough came through Ralph Gibson as a sudden experience. The impact of my first reading of The Somnambulist revealed complex ideas and a sense of mystery told in a fragmented narrative form—it unlocked a new way of seeing.

Later on, I remained grateful for his intellectual openness and honesty, as he looked back on his trajectory: grammar and vocabulary in Syntax, his path to a personal voice in Tropism, his life events in his “unauthorised autobiography,” Self-Expression and his theoretical framework and influences in Refractions 2. Even though my projects might not look like Gibson’s work, he remains a guide for me.

Ralph Gibson at the Confluence of Traditions

He started by drifting around photographing The Strip in LA in the early 1960s, rushing to join Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander, capturing life as it unfolded, Leica in hand, ready to react to serendipity. During a chance weekend at a lakeside house, the camera revealed something ambiguous he struggled to comprehend—a reflection of his inner world. The camera became a compass, pointed inward to explore perception and existential questions. This sparked the core of The Somnambulist and set him apart from the extroverted street photographers.

There are moments in an artist’s life when a sudden influence accelerates changes in the process. The documentary photographer, Dorothea Lange—whom he assisted in Los Angeles—introduced him to the notion of “point of departure,” unfolding an early concept during photographic exploration. Though he didn’t immediately abandon his “street photography flâneur” persona, this concept propelled him towards a more cohesive approach. It also helped to overcome the many pains of finding, executing and completing photographic projects. Embracing this idea, Gibson traced echoes of the pointed palm leaf through Egyptian culture and I investigated the way tropical light evokes emotional intensity in my series Citramarine.

His other mentor, Robert Frank’s The Americans influenced generations with an unsettling portrayal of American society and showed Gibson that a carefully sequenced narrative can convey complex emotions and personal truths. Yet, his visual grammar couldn’t be more different: while Frank’s images feel like spontaneous and urgent confessions, Gibson’s are meditative poems or visual metaphors. Taking the best of his masters but always with a personal twist.

As a student of art history, he was keenly aware of the rich formal legacy of American photography. His direct imagery and commitment to the integrity of the medium follow in the steps of Paul Strand, who took Steichen’s emphasis on clarity a step further to sharpen the objective power of the camera. Edward Weston’s sensuous photographs of sculptural beauty in everyday objects influenced Gibson's visual vocabulary. However, he went further with photographing classical art by juxtaposing these images to create counterpoints that construct multiple levels of meaning.

The integration of these distinct, parallel currents is clearest in his early photobooks—the three volumes of The Black Trilogy. By the early 1970s, he resolved this question I’m wrestling with here—how to arrive at a personal voice by building on influences, in a way that broadens the discourse. By consciously abandoning all the established styles, he forged his work into a new and distinct space. He played the abstract fragments against recognisable, almost straight renderings of human figures in The Somnambulist. To avoid the birth of “The Son of Somnambulist,” he changed his approach again and juxtaposed contradicting ideas in Déjà Vu to recall this little-understood psychological phenomenon. In the third volume, Days at Sea, he abandoned diptychs again, leaving the verso pages empty, using the fragmentary sequence to hint at a background story. It was exciting and offered a depth to discover, pointing to the need for constant reinvention.

Reading these books and understanding his emphasis on artistic autonomy, encapsulated in the mantra “all the credit, all the blame,” strongly reinforced my commitment to the photobook as my primary medium of expression. It represents a unique space for complete authorship, allowing me to shape the unfolding narrative fragments around a central theme, dictate the pacing, and engage with the tactile and design elements of the final piece. In this approach, editing is the heart of creating the work. It’s about creating dialogues between images that build upon each other and ultimately generate a more complex whole.

A Broader Web of Influences

But how did he build the courage to commit to his new way of seeing?

First of all, a voracious intellectual curiosity led him to the reassurance of some of the intellectual giants of continental Europe. He became interested in how photographs, image pairs and sequences create meaning and where this meaning originates in society or our consciousness, investigated by branches of philosophy like semiotics, structuralism, and phenomenology, the writings of Claude Lévi-Strauss, Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Jacques Derrida. Merging aesthetic exploration with theoretical inquiry opens a door to a more expansive conversation. In this framework, each photograph becomes a new question to explore, with intent, rather than the explicit subject matter taking central focus. The aim is to intrigue the viewer, encouraging them to actively decipher the “embedded meaning” and construct their interpretations.

Also, by surrounding himself with the best of the art world, he could swim in the currents outside of photography. Much of 20th-century art addressed similar concerns, and New York provided a fertile environment for Gibson’s development. Leo Castelli recognised his conceptual and visual depth, introducing his work to audiences more familiar with the paintings and sculptures of postmodernist revolutionaries. Friendships with cultural figures like Leonard Cohen, Andy Summers, and Eric Fischl fostered ongoing dialogues.

Cinema always played a huge role in his life. The disjointed narratives of Luis Buñuel—and even more so the French and Italian New Wave directors—deeply shaped his photobook approach. Inference by proximity, rather than explicit exposition. I’ve relied on these achievements to build the haunting world of my Jamais Vu series or the surreal narrative of Midnight Eclipse, centred around a rare astronomical event.

Extending beyond light-based mediums, the conceptual innovations of Marcel Duchamp, the recontextualisation of “found objects” deeply resonated with Gibson, and during his travels to his beloved France and Italia, opened up new avenues for thinking about photographic imagery. He implicitly affirmed my pursuit of photographing existing artwork, either by composing with a context that helps to distance it from the original creation, or by inserting the photograph in a sequence that creates the context.

This approach resonates with the experimental music of Heitor Villa-Lobos that accompanied Gibson in his years in the Chelsea Hotel on the way to The Somnambulist. Music led him to his "overtones theory," images placed next to each other creating “visual overtones,” new meanings created entirely in the viewer’s mind, that wouldn't be accessible in individual images. I’m grateful to play this instrument in diptych-based works like Citramarine or Jamais Vu.

Gibson’s Heritage

His commitment to his artistic voice and risk-taking ultimately led to a successful amalgamation of these diverse impacts. His influence continues to be felt, but the best of his students try to step out of the shadow of their master actively. Renato D’Agostin—Gibson’s assistant for over a decade—is perhaps the best example, who collaborated closely with curator Thierry Bigaignon to forge a distinct path while carrying forward certain essential visual principles. Another reason why D’Agostin became my second significant influence is his openness about his creative journey. His extensive documentation of his workflows, open photobook sharing, and discussions provide an invaluable window into his thought processes, revealing a remarkable intellectual generosity. Moreover, his candid acknowledgement of Gibson’s formative influence demonstrates that artistic lineage need not constrain originality but enrich the pursuit of individuality.

Points of Divergence

In my work, I never resisted his influence, because I never saw it as a stylistic model to emulate. Instead, I understand it as a conceptual framework—a “point of departure” rather than a destination. His work doesn’t prescribe a visual aesthetic for me to adopt; it offers a way of thinking about photography as an intellectual and emotional inquiry. Our lives were so different, the social, geographic, and personal distances so pronounced, that imitation was never a real danger. His influence doesn’t limit me; it liberates me to approach photography as an open-ended process, rooted in intention, ambiguity, and intellectual curiosity.

As an example of where my approach diverges, he underlined the paramount importance of personal style. Yet, I’m willing to sacrifice the benefits of a monolithic style and I prioritise visual decisions based on the needs of the project—an approach I believe I’ve carried from my experience in cinema. Directors and cinematographers, like Jean-Luc Godard or Roger Deakins, often emphasise the importance of the coherence of the world they operate in, the unity of form and content over a recognisable personal style. As my work naturally fluctuates between more introspective (The Floating World) and more documentary-based projects (under the working title Parallel Shores), I need to maintain this adaptability.

New Voices

Continuing with cinematic influences, Resnais's Last Year in Marienbad, and Nolan’s Memento, with their exploration of memory loss through fragmented sequences, are echoed in my BLACKOUT book, where I attempt to reconstruct a night’s lost memories using photographs, bridging real-world events, through the subjective nature of editing and sequencing.

The meditative pacing and desolation of Béla Tarr’s films, such as The Turin Horse, offer inexhaustible inspiration and remind me of the importance of occasionally holding back the pacing in telling a story.

When Bergman wrote about Persona, it taught me that art is often “in advance of the artist”—our best work may initially baffle us, and this ambiguity is something to be embraced. This also resonates with the surrealist strategies of automatism towards a deeper subtext.

On a more practical level, the methods and techniques of Hollywood filmmaking are the foundations of my approach to staying organised in both my archive and my artistic research.

Tracing the map of photographic influences beyond Ralph Gibson, I find Trent Parke, with his dramatic contrasts, masterful sequencing and world-building, encourages me to embrace raw, emotional intensity and to pay attention to the overarching structure of the sequence in my books like Midnight Eclipse and Undercurrents.

My earliest influence, the outstanding Taiwanese photographer, Chang Chao-Tang’s perspective summarised in the quote, “Photography is not for the satisfaction of others. Neither is it some kind of responsibility or mission. It is a means to fill a personal void.” validated my yearning to satisfy my personal need for expression.

Rudolf Arnheim’s theories on visual perception provide a crucial analytical layer. His conviction that visual expression is as much a product of cognitive processes as it is of aesthetic choices revealed why certain compositions compel viewers more powerfully than others. This has sharpened my attention to the psychological impact of structure, editing rhythms, and the subtle interplay of light and shadow.

From the heritage of traditional Japanese woodblock printing, the Ukiyo-e masters Kawase Hasui and Utagawa Hiroshige have informed my understanding of framing but more importantly—together with Chinese photographer Yang Yankang—became the “point of departure” for my series The Floating World, investigating the dualities of Ukiyo, the Buddhist world of sorrow and transience.

The powerful and unsettling Black Paintings of Francisco Goya encouraged me to explore presentation ideas for an upcoming exhibition that explores darker aspects of the human condition.

Lastly, I must also acknowledge the importance of champions and mentors like Szilvia Mucsy, contemporary photographer, festival director and curator, and PH21 Gallery, who both actively work to promote emerging artists both in Hungary and internationally. They provide invaluable support and guidance in moments where the work overwhelms the creator, underscoring the significance of an art community that fosters meaningful dialogue.

Turning to the Future

This evolving map of influence is not a closed system. It expands with each book and each new encounter. But even now, when I turn to trace the next path forward, I sometimes feel Gibson’s presence when I pull a copy of Deus Ex Machina or Days at Sea from the shelf—not to study like a textbook, but to reconnect. In his books, I find not a shadow, but a light on the horizon.

Andras Ikladi

Xiamen, China

2025.03.30